The Soul Survivors: How Brooklyn’s Historic Black Church Choirs Are Fighting to Keep the Faith — and the Choir — in a Gentrified City

When the Choir Gets Quiet, the Community Feels It

On a Sunday morning in Brooklyn, the sanctuary in our black church choir still fills with sunlight. The stained glass still catches it just right. The pulpit still stands firm. But if you listen closely in some historically Black churches across neighborhoods like Crown Heights and Bedford-Stuyvesant, something feels different.

The choir — once thunderous, multigenerational, and unmistakably alive — is quieter now.

This is not just about music. It’s about memory, migration, and what happens when the cultural heartbeat of a community is slowly displaced. The fading choir in Brooklyn’s Black churches has become one of the clearest signals of how gentrification, demographic shifts, and the aftershocks of the pandemic are reshaping spiritual life in the borough.

For generations, Black churches were not only places of worship. They were cultural anchors, political organizing hubs, music conservatories, and community safety nets. The choir was central to all of that — a living archive of struggle, joy, and collective survival.

Now, as Brooklyn changes, churches are being forced to ask hard questions: Who is still here? Who has been pushed out? And how do we hold onto tradition when the people who carried it are no longer in the pews?

A Pandemic, a Exodus, and a Quiet Shift in the Pews

COVID-19 didn’t start the decline in church attendance, but it accelerated trends that were already underway. Longtime Black residents, many of whom were the backbone of church choirs, were disproportionately affected by illness, death, and economic instability. Others relocated — pushed out by rising rents, property taxes, and the steady erosion of affordable housing in neighborhoods they helped build.

In Crown Heights and Bed-Stuy, once-dominant Black populations have thinned dramatically over the past two decades. As the demographics changed, so did Sunday mornings.

Churches like Concord Baptist Church of Christ — one of Brooklyn’s most historically significant Black congregations — have watched as their choirs aged, shrank, and struggled to replenish their ranks. Younger congregants often commute long distances, juggle multiple jobs, or feel less connected to institutional religion altogether.

The result isn’t abandonment — it’s fragmentation.

Why the Choir Matters More Than We Admit

To outsiders, the choir may seem like an aesthetic element of worship. To Black communities, it has always been something else entirely.

The choir taught discipline, collaboration, and emotional literacy. It offered young people a place to belong, elders a place to lead, and everyone in between a way to speak what couldn’t be said aloud. Gospel music carried theology, history, and resistance — all at once.

When choirs thin out, churches lose more than harmony. They lose a primary vehicle for intergenerational connection.

And once that bridge weakens, rebuilding it becomes exponentially harder.

Youth Perspectives: Faith Without the Familiar Soundtrack

For many younger Black Brooklynites, the relationship to church is complicated. Some still believe deeply, but don’t see themselves reflected in congregations that feel older, quieter, or disconnected from the realities of their daily lives. Others grew up watching churches struggle financially while neighborhoods transformed around them, leaving faith associated with loss rather than refuge.

Yet, interestingly, many young people still express nostalgia for the choir — even if they no longer attend regularly.

They remember the feeling. The swell of voices. The way the room shifted when the sopranos came in strong. The way gospel music made grief survivable.

This creates a paradox: the desire for the tradition exists, but the structure that sustained it is eroding.

Gentrification’s Spiritual Toll

Gentrification is often discussed in terms of housing and economics, but its spiritual consequences receive far less attention. When Black residents are displaced, churches are left ministering to shrinking congregations while sitting on increasingly valuable property — a tension that invites outside pressure, scrutiny, and sometimes predatory interest.

Some churches have sold buildings. Others have rented space to survive. A few have closed quietly.

Those that remain are adapting in real time, experimenting with smaller choirs, rotating singers, contemporary worship blends, and partnerships with community arts organizations. These efforts aren’t about abandoning tradition — they’re about keeping it alive under new conditions.

Short-Term Impact: Holding Services Together With Fewer Voices

In the immediate sense, churches are navigating logistical challenges. Fewer choir members mean fewer rehearsals, less musical variety, and greater strain on aging singers who continue to show up out of commitment rather than capacity.

Pastors and music directors are being asked to do more with less — emotionally, financially, and creatively. At the same time, churches are trying to remain welcoming to new residents who may not share the same cultural or religious background.

That balance is delicate, and often exhausting.

Long-Term Stakes: What Happens If the Choir Disappears?

If the trend continues unchecked, the long-term risk is not just the loss of music, but the loss of cultural transmission.

Gospel choirs are one of the last remaining spaces where Black sacred music is taught communally, across generations, without commercialization. When they disappear, so does a lineage that connects Brooklyn’s present to its past.

This isn’t inevitable — but it does require intention.

How Brooklyn Churches Are Fighting Back

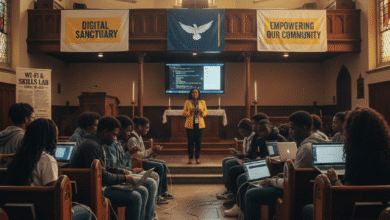

Some churches are responding with quiet innovation. They are:

- Reimagining choir membership to include commuters and hybrid participants

- Partnering with local schools and arts programs to introduce youth to gospel music

- Hosting community concerts and sing-alongs that lower the barrier to entry

- Using digital platforms to archive and teach choir traditions

These efforts reflect a deeper truth: survival doesn’t always look like preservation. Sometimes, it looks like translation.

What the Community Can Do Moving Forward

This moment calls for collective responsibility, not nostalgia alone.

Community members can support Brooklyn’s historic Black churches by attending services when possible, participating in cultural programs even if they no longer identify as religious, and advocating for policies that protect long-standing institutions from displacement.

For younger generations, engagement doesn’t have to mean full membership. It can mean showing up, singing once, volunteering skills, or simply acknowledging the value of what still exists.

The choir may be quieter — but it hasn’t stopped singing yet.

HfYC Community Poll of the Day

If gentrification keeps reshaping Brooklyn, can Black church traditions like the choir survive — or do they need to evolve to stay alive? Follow us and respond on social media, drop some comments on the article, or write your own perspective!

Alternative Perspectives:

- Is the decline of the Black church choir about faith — or displacement?

- Do younger generations want tradition, or something new that still feels like home?

- When the choir fades, what else do we risk losing?

Related HfYC Content

- Celebrating Black Joy in New Jersey’s Faith & Culture Spaces (Churches)

- Attacks on Christians in Nigeria – Hidden Truths & Political Lies

- Black Greek Life and Faith: Are Fraternities and Sororities at Odds with Christianity?

- Finding Our Reflection: Deconstructing the White-Washed Jesus

- Dating While Black and Christian: A Guide to Navigating Faith, Culture, and Love

- The Enduring Foundation: How New Jersey’s Black Churches Fueled a Movement and What That Means for Us Today

Other Related Content

- Concord Baptist Church of Christ – https://www.concordcares.org

- Brooklyn Historical Society – https://www.bklynlibrary.org

References (APA Style)

- Brooklyn Historical Society. (2023). Gentrification and cultural displacement in Brooklyn.

Pew Research Center. (2022). Religious participation trends among African Americans.

One Comment