The Media and the Mob

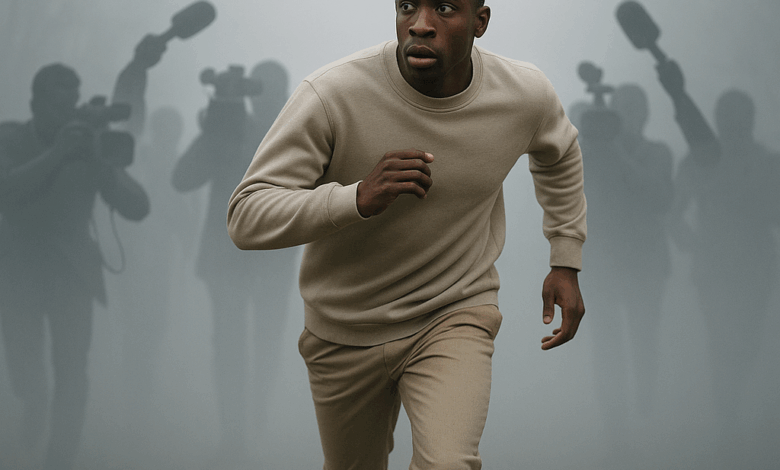

When scandal hits, it doesn’t unfold in a vacuum – it’s transmitted, magnified, and sometimes distorted by the all-pervasive media. Today, “media” is a hydra with many heads: from TMZ alerts pinging your phone, to think-pieces on The Shade Room, to viral hashtags on Twitter (now X), to CNN breaking news, to your cousin’s heated Facebook post. In high-profile cases like Diddy’s, the media can feel like both a spotlight of truth and a torch for a witch-hunt. So, how have media – both the predominantly white-owned outlets and the Black media sphere – shaped the narratives of these trials? And at what point does coverage cross the line from holding the powerful accountable to whipping up a destructive frenzy?

Let’s start with the obvious player in celebrity scandal: TMZ. TMZ is often the first to drop explosive tidbits – a leaked 911 call, an incriminating photo, a salacious rumor. They operate on the mantra “where there’s smoke, there’s fire… and we’ll film it.” In cases of Black celebrities, TMZ has been criticized for a certain gleeful tone. For instance, they infamously released the footage of Ray Rice (NFL player) knocking out his fiancée in an elevator, and closer to music, they often were first on R. Kelly updates and minor arrests of rappers. With Diddy, TMZ was surprisingly not at the forefront of breaking the Cassie story (perhaps because she filed quietly and it exploded via a reputable outlet). However, you can bet TMZ had sources sniffing around. They did publish stories about Diddy in the aftermath, including one about Cassie’s lawsuit and Diddy’s response, no doubt with their characteristic clickbait spin. The point is, tabloid media loves a fall from grace – and when the subject is a Black mogul, there’s an extra layer of spectacle, since it feeds into certain stereotypes their audience might have.

On the flip side, Black Twitter (the collective of Black voices on Twitter known for incisive cultural commentary) often functions as both media critic and amplifier. When Cassie’s allegations dropped, Black Twitter erupted in discussion. There was empathy (“We believe you, Cassie!”), there was anger (“Diddy been shady since forever, this ain’t surprising”), and there was skepticism (“Hmm, one day after filing she took the settlement, sounds fishy”). What’s important is that Black Twitter doesn’t speak with one voice – it’s a battleground of opinions. But it does tend to police narratives in a way mainstream media doesn’t. For example, when some outlets tried to paint Cassie’s lawsuit as a “money grab” using Diddy’s PR framing, many Black Twitter users clapped back, reminding folks of Diddy’s long-rumored history of violence and shady dealings (like old whispers about Kim Porter’s death or the Tupac/Biggie conspiracy). In a sense, Black Twitter often serves as a repository of communal memory that counters official PR. They’ll say, “Y’all surprised? We BEEN knew Puffy was on some devil time, remember the J.Lo era shooting, remember how he did Shyne?” etc., dredging up things mainstream reports might gloss over. At the same time, Black Twitter can also rally in defense – we saw some pushback against dragging Diddy too far before seeing evidence, and after the verdict, some voices saying “see, he wasn’t trafficking, media blew it up.”

White-owned media empires (your CNN, Fox, New York Times, etc.) have their own way of framing. Outlets like CNN and The New York Times reported fairly straightforwardly on the allegations and trial – sticking to facts, occasionally highlighting the shock value (CNN literally obtained and released the assault video). But consider Fox News or opinion sites: they might use a story like Diddy’s to subtly reinforce their audience’s biases. Fox, for instance, has historically reveled in covering Black celebrities’ misdeeds as a way to moralize or disparage Black Lives Matter or hip-hop culture in general. They might not say it explicitly, but the undertone is “Look at this rich Black thug – money can’t buy class or morality.” One has to be conscious of those dog whistles. The owners and editors of these media outlets decide which angles to emphasize. With Weinstein or Epstein, a CNN report might focus on systematic issues like “How did he evade justice for so long?” With Diddy, a similar report might sooner mention “the dark side of hip-hop’s glamour”. It’s subtle, but it frames the individual story as part of a broader commentary on Black entertainment culture rather than power culture.

Then we have specifically Black media outlets – like Ebony, Essence, The Root, BET, Hot 97 (radio), etc. These outlets often find themselves in a tough spot: wanting to support victims and truth, but also protective of Black icons’ legacies and wary of washing dirty laundry for mainstream consumption. Initially, some Black outlets were a bit muted on Diddy’s story; they reported it, but cautiously. After all, Diddy has been a benefactor or collaborator to many in Black media (Revolt is a Black media channel he started; he’s been a fixture at Essence Fest, etc.). But as details emerged, Black media did cover it with appropriate gravity. One notable thing: Black women journalists and commentators were at the forefront of saying “we must reckon with this pattern”. Publications like The Root published essays on how we must believe Black women like Cassie and stop putting moguls on pedestals. There was also commentary on how the Black community sometimes gives its male stars too many passes – a conversation that echoes what happened with R. Kelly, where black female journalists like Dream Hampton and Mikki Kendall were saying for years that we need to stop ignoring what’s in front of us.

This leads to the idea of the “media mob” – essentially cancel culture and online outrage. At what point does legitimate criticism become a punitive mob with pitchforks? With Cosby, once about 20+ women had spoken out, the media mob was in full swing: reruns pulled off air, his honors revoked, people literally taking sledgehammers to his Hollywood star. Few were arguing for restraint. With R. Kelly, by the time #MuteRKelly trended, the mob (led by Black women) effectively cancelled his airplay and concerts. In retrospect, those mobs feel justified because these men were indeed found to have done terrible things. But are there cases where the mob went too far on perhaps flimsy evidence? Some would argue Michael Jackson experienced a sort of media mob justice especially after his death via the Leaving Neverland doc – where his music was briefly blacklisted on some stations despite him not being able to defend himself, based solely on the testimonies of two men (which some fans contested with counter-evidence). The risk of a mob mentality is that it doesn’t wait for due process; it anoints itself judge, jury, and executioner in the court of public opinion.

Social media accelerates this. An unverified claim can go viral and ruin a reputation in hours. There is a constant tension: We want to believe survivors and hold predators accountable, but we also know false or exaggerated accusations can happen (albeit rarely in these big cases). The question “When does coverage become a witch-hunt?” is crucial. Perhaps when the tone shifts from seeking truth to seeking blood. One can observe, for example, how some YouTube and Instagram commentators started speculating wildly about Diddy: tying him to every bad event (from Tupac’s murder to ex-girlfriend Kim Porter’s untimely death), creating a narrative that he’s basically an evil overlord. There were even conspiracy theories that Diddy was involved in some occult or that this was karma for something unrelated. Those leaps go beyond the Cassie case into the realm of witch-hunt – everything bad must be true about him because one bad thing was alleged.

We saw similar with Michael Jackson – once accused, there were folks convinced he must also have done X, Y, Z, and even innocuous behavior (like him having kids at Neverland) was seen as sinister by default. With Cosby, after the main allegations, even clearly consensual extramarital affairs he had were reinterpreted by media outlets as further evidence of his deviance, muddling the narrative (infidelity isn’t a crime, but it was reported alongside assault allegations to paint a fuller negative picture). It’s like once the media machine has a villain in its sights, it starts gathering all the sticks to burn him at once – even irrelevant ones.

For Black celebrities, there’s also the fear of overkill: the sense that the media will drag a Black star extra hard for clicks. For example, when Chris Brown assaulted Rihanna in 2009, it was huge news (rightly so). But some pointed out how Charlie Sheen, who shot a girlfriend and has multiple abuse allegations, never got the same sustained “cancel” treatment – he went on to get a TV show, etc., while Chris Brown is still dogged by that incident in headlines over a decade later. It’s a tricky comparison, but it feeds perception that Black men don’t get to outlive their sins in the media’s eyes, whereas some white men do.

Another aspect: who controls the narrative? Often, it’s the big media companies (largely white-owned) that decide how much airtime or ink to give something. The fact that Leaving Neverland (MJ doc) got massive promotion on HBO, while a defensive counter-documentary made by his family got little attention, shows the power imbalance. Similarly, Diddy’s accusers got a platform through major outlets, but if Diddy had defenders, their voices were less amplified (apart from his lawyers’ statements). In Weinstein’s case, media sided with accusers strongly – but Weinstein also had the New Yorker and NY Times basically championing the cause. In Cosby’s case, aside from his publicist ranting, few spoke for him; the coverage was almost uniformly against him (again, arguably for good reason given volume of evidence).

Black Twitter and Black media often try to reclaim narratives to ensure fairness or context. For instance, during Cosby’s trial, some Black commentators reminded us that “hey, prosecute Cosby, but why is Roman Polanski still getting Oscars?” – highlighting a double standard in media outrage. During R. Kelly’s exposes, people asked “why did it take lifetime (a network) to do this? we knew this in the 90s, but mainstream media ignored it because the victims were Black.”That’s a media failure too – it took a village of online voices to pressure news outlets to care.

The concept of a “witch-hunt” historically implies fervor to punish without fair evidence, often out of moral panic or prejudice. Are these high-profile cases witch-hunts? It depends who you ask. Diddy’s supporters might call the flood of lawsuits in late 2023 a witch-hunt orchestrated by opportunists and feds looking to make an example out of a Black mogul. The accusers and their supporters would say it’s simply long-overdue justice. There’s a line: a witch-hunt targets the innocent. If one is guilty (at least in part), is it a witch-hunt or just a hunt? However, it can feel witch-hunt-y if the punishment in public discourse far exceeds what’s proven. For example, Diddy being labeled a “sex trafficker” in headlines for months until trial, when ultimately he wasn’t convicted of that, might seem unfair to his image (though one could argue his own actions warranted the label initially).

One might consider the case of Russell Simmons as another example: he faced multiple sexual assault allegations during #MeToo, and a documentary On The Record about one accuser premiered on HBO Max. Simmons denied it all and moved to Bali (which has no US extradition). Media covered it but then it faded; no charges filed. Some view him as a likely abuser who escaped, others think he was unfairly maligned. The media memory is ambiguous there – he’s not in jail, but his reputation in many circles is ruined. Is that justice or mob verdict? Hard to say.

All of this underscores that media has immense power to shape public perception before any judge’s gavel falls. They can cast someone as a pariah overnight. They can also choose to downplay something. Jeffrey Epstein’s story was actually squashed by some media earlier (an ABC reporter said her higher-ups killed the story years before it blew up latimes.comlatimes.com). So media can either be complicit in silence or aggressive in exposure. Often depends on whose ox is being gored and what sells.

The legacy of Elvis Presley offers a stark comparison. Presley famously began a relationship with a 14-year-old Priscilla Presley, yet he remains an American cultural icon, scarcely subjected to the lasting vilification that now shadows R. Kelly. This disparity highlights a racial double standard: Elvis’s indiscretions are treated as footnotes, whereas Kelly’s are defining features.

The presence of “white media empires” in narrative shaping cannot be overstated. Companies like Disney (which owns ABC), Comcast (NBC), Viacom (CBS, BET), News Corp (Fox, NY Post) – these giants have predominantly white leadership. Their outlets decide narratives. For example, NBC was accused of spiking Ronan Farrow’s initial Weinstein story – some say to protect powerful friends. If Diddy had deep ties at a network, could that network soften coverage? Possibly, but Diddy’s influence doesn’t extend that far. Conversely, when Kanye West made anti-Semitic remarks, the media space (which has many Jewish leaders) reacted strongly and swiftly in condemning him. In contrast, when racism is inflicted on Black people, sometimes media is slower or more muted (e.g., few mainstream outlets originally amplified the story of police not investigating Black women’s claims against a wealthy white offender, etc.). This difference can feed a feeling that the media is not “ours” and can’t always be trusted with our narratives.

Bringing it back to the topic at hand: In Diddy’s trial, media coverage was significant but nowhere near, say, O.J. Simpson levels. It was a big story on day one of Cassie’s suit, and on verdict day it made headlines (Reuters, AP, etc. had breaking news). But cable news wasn’t 24-7 on it; it was more an entertainment news item. Why? Possibly Diddy’s story, while big in music, doesn’t have the cross-demographic intrigue of a Michael Jackson or the political implications of a Trump. Still, within Black media and social media, it was a huge conversation. And there, one could argue, a bit of a mob formed with people recounting every rumor they ever heard about Diddy (some even dredging up the old gossip of him being involved in Tupac’s murder as if to further damn him – unrelated but illustrative of how once a man is down, everything becomes fair game to throw at him).

When does it become a witch-hunt? Maybe when evidence or due process no longer matters to the discourse – when, in the eyes of the public, the accused is as good as convicted of anything and everything, without room for nuance. There’s a danger in that, obviously: we don’t want to become a society that executes by public opinion. At the same time, public opinion can also force action when institutions fail (as with R. Kelly, public pressure finally spurred law enforcement). It’s a double-edged sword.

One approach to avoid witch-hunts is for media (and us consuming it) to maintain a level of fairness and facts-based critique. That means acknowledging when an accused has been found not guilty of something and not ignoring that because it doesn’t fit the juicy narrative. For example, after Diddy’s verdict, do headlines highlight he was acquitted of sex trafficking (which would slightly soften the monster image), or do they focus on “guilty of prostitution counts” only? Reuters and AP did mention the acquittal prominently reuters.comreuters.com, which is responsible. But some social media chatter ignored that and still call him a “sex trafficker.”

Furthermore, the role of media ownership and race plays into the notion of “taking down powerful Black celebrities” that our thesis posits. If most major media is not Black-owned, then narratives of Black success and Black scandal are often filtered through a non-Black lens. That lens might be prone to sensationalism or lacking cultural context (e.g., not understanding what a “freak-off” entails culturally, or exaggerating its uniqueness). Black-owned media (like Diddy’s own Revolt, or black-run blogs) might frame it differently or choose different emphases. But with Diddy, even Revolt had to report on their founder stepping down temporarily people.compeople.com.

It’s also worth noting how social media outrage can compel corporate reactions: When the Cassie allegations hit, brands like Cîroc vodka and DeLeón tequila (which Diddy represents) had to assess their association. Cîroc’s parent (Diageo) was already in a legal spat with Diddy accusing them of racism (that’s another story), but public pressure in scenarios like these can lead to dropped endorsements, etc., even before a verdict. That economic fallout is part of the media mob effect. We saw Adidas drop Kanye, Netflix shelve projects with Will Smith after his Oscars slap – not criminal, but public furor caused immediate consequences. For Diddy, in the wake of allegations, some ventures paused. For example, he “stepped down” from Revolt network leadership people.compeople.com and reportedly his name was quietly removed from some business dealings. This is informal punishment delivered by the court of public sentiment and risk management.

In closing this section, one might ask: how do we get reporting that’s just, and not a frenzy? It requires balance and a focus on truth over sensation. It means Black media continuing to speak up so that stories like these are covered with community insight and not just outsider gawking. It means us, as consumers, checking ourselves: are we retweeting something because it’s verified or just scandalous? Are we part of a constructive conversation or a digital lynch mob? And importantly, are we keeping the same energy for all abusers, not just the ones who fit a convenient narrative?

The media and the mob together can be a force for accountability, as seen by exposing these powerful men, but they can also become a runaway train that conflates justice with spectacle. As we engage with these stories, we should ask: Am I seeking understanding and justice, or just entertainment and vengeance? It’s a tough reflection. But our community’s stories deserve to be told fully – not sanitized to protect reputations, and not exaggerated to fit stereotypes. The truth, as always, should be enough.

Conclusion

As the dust settles on Sean “Diddy” Combs’ partial conviction, and as Black America processes yet another superstar brought low by scandal, we find ourselves at a crossroads of reflection and reckoning. What does all this mean for Black creatives and moguls moving forward? How do we as a community protect the vulnerable among us while still guarding against the outside world’s eagerness to topple our heroes? In essence: Can we hold our own accountable and still shield them from unjust takedowns?

First, let’s acknowledge the progress embedded in these painful stories. There was a time not long ago when a woman like Cassie might never have spoken out – or if she did, she would have been dismissed and discarded. The fact that Cassie’s voice was heard, that legal actions were taken, that survivors of all backgrounds are finding solidarity, signifies a shift. This is what justice could look like: not the simplistic happy ending, but a world where even the rich and famous face consequences, where a victim’s trauma isn’t invalidated by her perpetrator’s status. Black women, in particular, have often felt unprotected both by society and their own community. The Cassie case, coming on the heels of #MeToo, suggests that maybe Black women’s accusations will finally receive the gravity they deserve cbsnews.com. That is a form of justice we cannot overlook – it means our daughters might not have to suffer in silence.

However, there’s a counter-truth: Justice, as currently delivered, is imperfect and often incomplete. Diddy was convicted of something, yes, but many feel he evaded the full weight of his sins. Michael Jackson died without a legal reckoning, leaving victims (if you believe them) without closure, and his defenders without definitive vindication either – a purgatory of uncertainty. R. Kelly and Bill Cosby eventually went down, but only after decades of harm that could have been curtailed if we had intervened sooner. And countless others – from lesser-known predatory executives to possibly complicit crew members – have not faced any scrutiny at all. So while we celebrate newfound accountability, we must also admit that our justice system and social condemnations often come too late or with too many loopholes.

So, what now? For Black creatives and moguls who are forging their path today, the lessons are stark. With great power comes great responsibility – and great scrutiny. If the old model was that you could use and abuse behind closed doors and be shielded by fame, that model is crumbling. The new reality is this: if you engage in exploitation, it will eventually come to light. It might take a year, it might take 30 years, but the odds are no longer in favor of eternal secrecy. Some young artists have taken heed – you see more open conversations in hip-hop about mental health, respect, even consent. But others still fall into the trap of entourage culture and its excesses. Moving forward, Black moguls who truly care about their legacy need to build internal checks. That could mean keeping people around who aren’t yes-men, who can say “Yo, that’s not cool” and be listened to. It could mean actively creating safer environments for colleagues and fans – for example, having protocols at parties to ensure no one is too out of it to consent, or simply treating those who work for you with basic respect so they don’t fear or revere you to the point of complicity.

For the Black community at large, these high-profile falls present a challenge of narrative. The thesis at the beginning posited that our own broken culture is weaponized against us – that when our celebrities slip, the blowback not only hits them but serves as indictment of Black culture, making it “easy for racism… to take down powerful Black celebrities.”How do we combat that? Perhaps by changing the culture ourselves before it becomes a weapon. If we stop “perpetuating” some of the harmful aspects – the misogyny, the hush-hush mentality, the hero-worship – then there’s less for detractors to latch onto. It’s like cleaning your house so the inspector has nothing to fault. This is reflective, not prescriptive: we have to want that change internally. It means grappling with uncomfortable truths like we did earlier – admitting that Freaknik and Black Bike Week, for all their fun, also sowed seeds of permissiveness that bad actors exploited.

At the same time, we must guard against the external double standards and gleeful persecution. One way to do that is to maintain ownership of our narratives. If a Black mogul is accused, it should be Black journalists and community leaders at the forefront of investigating and, if warranted, condemning. That robs the mainstream of the chance to say we ignore our own problems. It also means when one of our folks is falsely accused or excessively punished, we rally with facts and support. We have to be discerning – not every Black man accused is a martyr of racism (some are just guilty), but if one is clearly being used as a scapegoat or getting harsher treatment than white counterparts, we should loudly point that out. This is how we protect against unjust takedowns: by demanding equal treatment. If Cosby’s in prison (at the time) and Weinstein is too, fine – equal. But if Cosby were in prison and a similar white celeb roams free for the same stuff, that’s a problem to call out whyy.org. In Diddy’s case, one could argue the system actually gave him a fair shot – he fought in court and partially won. So the answer isn’t to reflexively cry racism whenever a Black star is charged; it’s to analyze the situation critically and ask, would a white person in this position be treated the same by media and law? If not, raise hell. If yes, then it’s not a takedown because he’s Black; it’s likely consequences because of actions.

A crucial part of moving forward is education and empowerment. We must educate upcoming artists, athletes, and entrepreneurs about the traps of fame. Many of our stars come from humble or chaotic backgrounds and are suddenly handed money, adoration, and lack of boundaries. That can distort anyone’s moral compass. Mentorship programs, for example, where older reformed celebs talk to younger ones about how to handle groupies, how to treat people, how to avoid yes-men and maintain normalcy – these could help. We often emphasize financial literacy for young Black celebs (so they don’t go broke); perhaps we need ethical literacy too: how not to lose yourself and your values when you “make it.” Prince, in a sense, had that literacy – he knew what he stood for and didn’t waver. Others got lost in the sauce.

From a community perspective, maybe we ought to reaffirm what kind of behavior we will not tolerate from our “faves.” It might mean sacrificing some music or films we love because the person behind them did awful things. It’s hard – people still dance to “Step in the Name of Love” at weddings even after R. Kelly’s conviction, because the cultural attachment is strong. But perhaps over time, we recalibrate and say: “We’re done elevating people who hurt us. Talent isn’t an excuse to harm.” If we hold our own accountable first, it leaves less room for an opportunistically racist system to do it for us in a way that harms the entire community’s image.

In closing, I want to strike a tone of concern laced with hope and love. It is with deep care for our community that I say we have to face these toxic elements honestly. We have to hold our brothers (and sisters, in some cases) to a higher standard of conduct because we love them and want them to thrive genuinely – not on a throne built on others’ pain. We also must hold ourselves accountable: for supporting problematic behavior in the past, for staying silent when we should have spoken. It’s okay – we didn’t always know better, but now we do.

At the same time, let’s not let the narrative of Black moguls be only one of tragedy and disgrace. For every Diddy or R. Kelly, there are positive examples too – folks who used their power to uplift, who navigated fame without (known) scandal. They just don’t make the news as often. We should highlight and learn from those stories as well, so the next generation sees that it’s possible to be wildly successful and righteous in how you wield power.

Maybe the ultimate justice is this: ensuring the world we create for our sons and daughters is one where they don’t have to choose between fun and safety, between success and integrity. A world where a young Black woman can pursue her dreams in entertainment without facing a predator at every turn. A world where a young Black man can enjoy his success without the temptation or pressure to prove himself through sexual conquest or intimidation. A world where our culture’s house – once marred by those toxic elements – is renovated into a home of creativity, respect, and accountability.

Before we end, I’d like to leave you with a gentle call to reflection: Think about the music, the films, the events that shaped you. What did you absorb from them about gender, power, and respect? What would you keep, and what would you change for the next generation? These are not easy questions, but they are necessary ones.

Our community is resilient – we have survived centuries of external oppression. The internal battles, like the one for our cultural soul amid fame and fortune, are ones we can win. But it starts with honesty, love for one another, and the courage to say “we can do better, for us.”

So as we close the chapter (for now) on Diddy’s saga and similar trials, let’s not just scroll to the next scandal. Let’s carry the lessons with us. Let’s ensure that power is checked by principle, perception is guided by truth, and punishment – when needed – is given with justice, not malice. If we can do that, we will have turned these tragedies into catalysts for growth. And that, more than any verdict, will be the real justice and healing our community needs.

“If you don’t own your masters, your master owns you.” – Prince

Prince’s reminder was about music rights, but in a broader sense, it speaks to owning our culture and narrative, lest they own us. May we own up to our responsibilities so that no outside master – be it vice or prejudice – ever owns our destiny.) latimes.com

The Diddy Article Series:

- Part 1/3 – Power, Perception, and Punishment: The Trial of Diddy and the Question of Justice for Black Moguls

- Part 2/3 – Cultural Dynamics & the “Hip Hop House”

- Part 4/4 – Coming Soon – December 10th

One Comment