Finding Our Reflection: Deconstructing the White-Washed Jesus

From Sunday school classrooms to stained-glass windows, many Black Christians grow up with an image of Jesus that looks like everything—but rarely like us. Yet, faith should reflect our image just as much as it reflects God’s. This tension, that of deconstructing the white-washed Jesus, is not merely about aesthetics. It’s about identity, theology, belonging, and whether we truly see ourselves as made in God’s image.

In this essay, we’ll journey through:

- the historical and cultural roots of a whitewashed Jesus

- biblical and African presences in Scripture

- youth perspectives on representation in faith

- the short-term and long-term effects on community

- and how we can reclaim a faith that honors our reflection in Christ

The Roots of a White-washed Jesus

Why did Jesus’ image get “whitened”?

The familiar portrait of Jesus—with fair skin, European features, and flowing light hair—didn’t emerge in first-century Palestine. Rather, it is the product of centuries of art, colonial power, and cultural hegemony. During the European Renaissance, artists painted sacred figures in their own likeness: white, Western, and aristocratic. These images traveled via colonial mission, church architecture, Christian art, and media. Over time, they shaped the collective imagination—even in places far removed from Europe.

This phenomenon is not an innocent aesthetic preference. In Christian-majority societies, the white Jesus reinforced the idea that whiteness was normative, sacred, and divinely authored. To be nonwhite was to stand outside that default. Many Black Christians internalize this, sometimes unconsciously, as a theological dissonance: I believe Christ died for me, but I rarely see myself in Christ.

That divide matters deeply.

- Filename: simon-cyrene-african.jpg

- Alt Text: “Simon of Cyrene carrying Jesus’ cross, highlighting African presence in the crucifixion narrative.”

Biblical and African Reflections in Scripture

What does Scripture say about presence, diversity, and identity? Far more than we often realize.

Simon of Cyrene and North African Presence

One of the most powerful reminders that Jesus’ story is part of a global, multiethnic narrative is Simon of Cyrene. In the Gospels, during the crucifixion, Roman soldiers compel Simon of Cyrene (a man from North Africa) to carry Jesus’s cross (Mark 15:21; Matthew 27:32; Luke 23:26).

Cyrene was a city in what is now Libya—North Africa—and had a significant Jewish diaspora presence. Mark even identifies Simon as “the father of Alexander and Rufus,” which suggests his family was known to early Christian communities.

While the Gospels do not explicitly describe his skin color, Simon’s inclusion in the story invites us to see a Black or African-located person at a critical moment. His forced action becomes a symbol: the cross burden was shared. The redemption narrative was never limited to one geography or one skin.

Ethiopian Eunuch, Luke, and the Global Gospel

In the Book of Acts (Acts 8:26–40), Philip meets an Ethiopian eunuch, an African official, who is reading Isaiah in his chariot. Philip explains the good news of Jesus, and the eunuch responds by receiving baptism. This story illustrates:

- The early spread of faith into Africa.

- The legitimacy of African converts in the first century.

- The idea that Jesus’ message reaches beyond Israel, transcending ethnicity.

These biblical touchpoints challenge the narrative that Jesus belongs only to Western or European imagination.

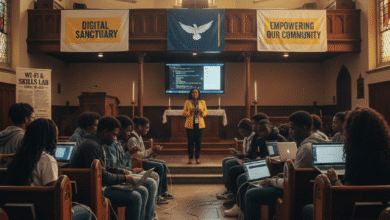

Youth Voices & the Search for Identity in Faith

Why does representation matter to younger believers?

For many Black youth, faith is not just theology—it’s identity formation. When the face of Christ looks nothing like their own, it becomes harder to internalize that faith is inclusive and that God sees them.

Young believers share:

- Alienation in worship spaces: “When all the murals show a Euro-Christ, I feel like I’m an outsider in my own church.”

- Doubt and dissonance: “If the Savior doesn’t look like me, am I allowed to imagine God’s love fully for me?”

- Desire for authenticity: Many ask for diversity in worship art, in sermon illustrations, in statues — even liturgical language that says “Jesus of Nazareth, a Middle Eastern Jew” rather than “White King on a throne.”

- Reclaiming own imagery: Some are creating Afrocentric artwork, gospel albums, and youth group visuals that show Jesus with African features or skin tones that reflect diaspora communities.

Older generations, too, carry wounds — some were taught a monolithic Christ-image and now wrestle to reframe it. Yet many are open, hopeful, and sincerely want the next generation to see themselves clearly in faith.

Immediate & Long-Term Impacts on the Community

Short-Term Effects

- Spiritual disconnect: Some believers struggle with feeling “less seen” or assume God doesn’t fully understand their lived experience.

- Faith doubts: Youth may question whether Christian narratives truly include them.

- Cultural conflict: Parental or institutional pushback may arise when new imagery or critiques of traditional art are introduced.

- Fragmented worship spaces: Churches that cling to Eurocentric visual traditions may alienate young people or newcomers of color.

Long-Term Consequences

- Generational theological gap: If successive generations don’t feel seen, church retention drops, or faith becomes compartmentalized.

- Lost prophetic voice: A church that fails to represent diversity internally is weaker in advocating for justice externally.

- Narrow imaginations of God: Communities may unknowingly limit how they preach about God’s character, miss cross-cultural connections, or avoid challenging power structures.

- Artistic and cultural poverty: Over time, communities may lose capacity or confidence to produce their own sacred art, leaning always on imported or externally framed Christian visuals.

How to Reconstruct & Reclaim a Reflective Faith

Steps toward a theology that sees us

- Educate with truth: Offer sermon series and teaching on biblical diversity, African Christian roots, and the global church. Highlight lesser-known biblical figures from Africa or non-Jewish contexts (e.g., Simon of Cyrene, Ethiopian eunuch).

- Commission new imagery: Ask local Black artists to depict Jesus, saints, and biblical scenes with diasporic faces.Replace or supplement traditional murals, stained-glass windows, and worship slides with diverse visual imagery.

- Invite critical dialogue: Host panels with youth, theologians, and church leaders to discuss representation in faith. Make safe spaces for people to share how whitewashed Christ-images have affected them.

- Center Imago Dei in teaching: Emphasize that all humans bear God’s image — Black bodies as much as any — resisting theology that uplifts only whiteness. Teach that redemption is cosmic, multiethnic, and rooted in diversity.

- Mentor cross-generational art & theology: Create collaborative projects where older and younger believers produce liturgy, worship art, poetry, and music that reflect diaspora identity. Preserve memory and heritage—not by erasing older practices, but by expanding them.

- Adopt inclusive worship practices: Use liturgical language that acknowledges Jesus’ Jewish Palestinian context. Rotate imagery, art, and iconography to reflect global Christian expression.

- Filename: diverse-christ-art-gallery.jpg

- Alt Text: “Youth and congregation observing Jesus depictions in diverse skin tones — reclaiming representation in faith.”

Key Takeaways

- The image of Jesus many know is a cultural artifact, not a biblical necessity.

- Scripture affirms that African presence (Simon of Cyrene, Ethiopian eunuch) is part of the gospel story.

- Representation in faith matters deeply to youth, identity, and community belonging.

- Ignoring visual diversity in church has both immediate spiritual costs and long-term theological consequences.

- Reclaiming a reflective faith is possible through education, art, dialogue, and intentional worship practices.

Call to Action: Next Steps for Readers & Communities

- Church leaders: Start sermon series or small groups exploring biblical diversity and representation.

- Youth & artists: Create and share artwork, worship visuals, and curated media that recenter Black and diasporic reflections of Christ.

- Congregations: Review worship spaces—murals, stained-glass, projected slides—and intentionally diversify them.

- Individuals: Be curious. Ask questions. When you see a whitewashed Christ in your church, speak up.

- Share & connect: Use hashtags, community groups, or HFYC share spaces to showcase new imagery, reflections, and reclaimed narratives.

Embracing a faith that truly reflects all of us is a sacred act of reclamation. When Black children see Christ in faces that mirror theirs, when whole communities feel seen and affirmed, that is not a small thing — it is gospel.

Related HfYC Content

- (https://hereforyoucentral.com/faith-and-identity)

- (https://hereforyoucentral.com/community-storytelling)

- (https://hereforyoucentral.com/black-mental-wellness)

Other Related Content

- (https://www.hnn.us/article/the-long-history-of-how-jesus-came-to-resemble-a-w)

- (https://thejesuitpost.org/2021/06/the-problems-with-white-jesus/)

References (APA Style)

- Got Questions Ministries. (n.d.). Who was Simon of Cyrene? GotQuestions.org. Retrieved October 12, 2025, from https://www.gotquestions.org/Simon-of-Cyrene.html

- Got Questions Ministries. (n.d.). Who was the Ethiopian eunuch? GotQuestions.org. Retrieved October 12, 2025, from https://www.gotquestions.org/Ethiopian-eunuch.html

- Stockton, R. (2022, January 13). Why is the world filled with depictions of a white Jesus when the history says otherwise? All That’s Interesting. https://allthatsinteresting.com/white-jesus

- Viladesau, R. (2020, July 15). The long history of how Jesus came to resemble a white European. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/the-long-history-of-how-jesus-came-to-resemble-a-white-european-142130 (Originally published on HNN.us)

- Wikipedia contributors. (2025, October 1). Simon of Cyrene. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Simon_of_Cyrene

- Wikipedia contributors. (2025, September 28). Ethiopian eunuch. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ethiopian_eunuch

3 Comments