The Enduring Foundation: How New Jersey’s Black Churches Fueled a Movement and What That Means for Us Today

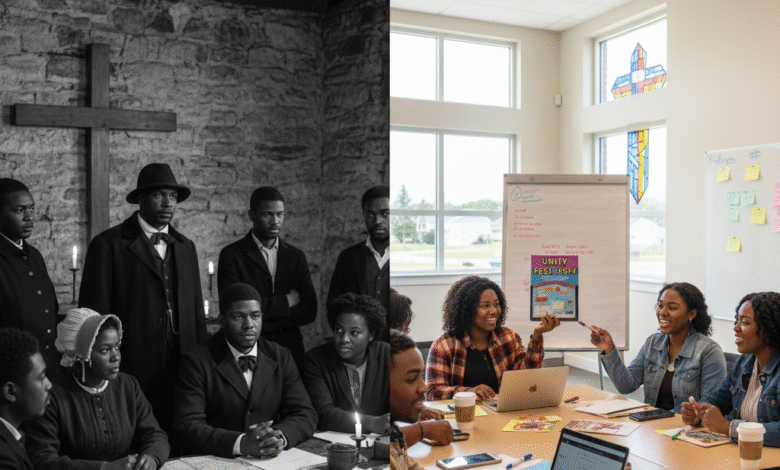

Step inside the sanctuary of a historic Black church in New Jersey, and you’ll feel it. It’s in the worn wood of the pews, the vibrant colors of the stained-glass windows, and the echoes of hymns that have filled the space for generations. But listen closer. Beneath the melodies, you can hear the whispers of freedom seekers finding refuge, the strategic planning of Civil Rights leaders in hushed basements, and the powerful prayers of a community forging its own destiny. This is more than just a house of worship. This is a command center, a school, a sanctuary, and the unwavering backbone of the Black freedom struggle.

In a state often called the “Georgia of the North” for its complicated and often harsh racial history, the story of Black progress is inextricably linked to the rise of its faith institutions. The history of

Black churches in New Jersey is a powerful testament to how faith becomes action. From their fiery origins as acts of radical self-determination to their role as the epicenter of social change, these sacred spaces have been the engine of Black life and liberation. Today, as a new generation poses critical questions about faith and justice, this legacy offers a profound roadmap for our future, challenging us to understand where we’ve been to truly know where we’re going.

Forged in Freedom’s Fire: The Birth of New Jersey’s Black Church

The Black church in New Jersey wasn’t born out of convenience; it was forged in the fires of resistance. In the early 1800s, many Black and white residents worshiped together. However, as the abolitionist movement gained momentum, white Methodist congregations, particularly in South Jersey, began to buckle under pressure from slaveholding members and wavered in their anti-slavery stance. This wasn’t a friendly parting of ways; it was an expulsion, a moment when Black parishioners were told their fight for freedom was no longer welcome in God’s house.

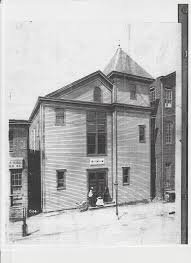

Their response was nothing short of revolutionary. Instead of seeking acceptance elsewhere, they built their own. In 1810, after being forced from their local Methodist church, Black congregants in Greenwich Township formed the “African Methodist Society”. By 1817, they officially joined the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) denomination founded by the visionary Richard Allen, establishing what is now known as the

Bethel AME Church in the free Black community of Springtown. This was not merely a religious split; it was a strategic political act. It was the creation of an autonomous institution—a Black-owned, Black-led space where the community could control its own finances, property, and political agenda, free from the white gaze.

These new churches immediately became the critical infrastructure for liberation. They were the secret, sacred stations on the Underground Railroad.

- Bethel AME Church in Springtown became a key stop on the “Greenwich Line,” a route operated by Harriet Tubman herself, who lived and worked in the area while guiding people from bondage in Maryland and Delaware to freedom.

- In Camden, the Macedonia AME Church, established in 1832, served as a safe house under the leadership of Reverend Thomas Clement Oliver, one of the state’s most important Underground Railroad operatives.

- The Mt. Zion AME Church in Woolwich, founded in 1799 in a settlement created by anti-slavery Quakers, was built with a trap door under its vestibule—a literal gateway to freedom for those escaping the horrors of slavery.

These were not just churches; they were parallel power structures, the first Black institutions built to sustain a movement.

The Command Center for Civil Rights

As the fight for freedom evolved from abolition to the Civil Rights Movement of the 20th century, the role of New Jersey’s Black churches shifted from clandestine safe houses to public headquarters for social change. The battle for equality was not confined to the South; it raged fiercely in the “Georgia of the North,” and the church was the command center.

When Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) needed a base in Newark, and some established Black Protestant churches hesitated, it was a Black Catholic church that answered the call. The

Queen of Angels Catholic Church, the first African-American Catholic parish in the city, bravely opened its doors, becoming the SCLC’s New Jersey headquarters. In 1968, it did so again, serving as the headquarters for the Poor People’s Campaign. Dr. King himself visited the church just one week before his assassination, a testament to its central role in the national movement.

This institutional courage was possible because the Black church was accountable only to its congregation and its conscience. Financially and socially independent from the white power structure, it could take risks others could not, making it the ideal vehicle for mobilizing the community. It was from the pulpit that pastors disseminated information, organized voter registration drives, and inspired congregants to action.

And it was often Black women who were the architects of this activism, using the church as their organizational base. Women like Violet Johnson and Florence Randolph in Summit challenged racial and social norms through their faith.Organizations like the Women’s Fortnightly Club, born out of St. Augustine Presbyterian Church in Paterson, became powerful forces for community uplift. The church provided the space and the spiritual grounding for these women to lead, organize, and build the foundations of New Jersey’s freedom struggle.

The Heartbeat of the Community: A Legacy of Service

While its role in the political struggle is legendary, the Black church’s impact has always been more holistic. It is the heartbeat of the community—the place for baptisms, weddings, and funerals, but also the provider of essential services that the system often denied.

From their earliest days, Black churches in New Jersey established schools, founded community organizations like Paterson’s Colored Y.M.C.A., and even launched medical clinics and credit unions. This legacy of holistic care is alive and well today, woven into the fabric of communities across the state.

- In Newark, the Metropolitan Baptist Church runs the Willing Heart Community Care Center, a beacon of hope that offers a food pantry, soup kitchen, clothing for those entering the workplace, and safe recreational programs for youth.

- In Trenton, the historic Shiloh Baptist Church operates a community development corporation focused on family health, running programs to improve maternal and infant outcomes and hosting vital public health services like COVID-19 vaccination clinics.

- In Englewood, the Community Baptist Church lives out its mission of “Serving the Community by Faith” through robust ministries that support teens, men, and the wider community.

These institutions, and hundreds like them, are living proof that the church’s work extends far beyond Sunday morning. To connect with this incredible history, you can explore the landmarks that still stand as monuments to faith and freedom.

| Church Name | Location (City, County) | Historical Significance |

| Bethel AME Church | Springtown, Cumberland County | Oldest AME congregation in NJ; key stop on the Underground Railroad operated by Harriet Tubman. |

| Macedonia AME Church | Camden, Camden County | Oldest Black church in Camden; used as a safe house on the Underground Railroad. |

| Mt. Zion AME Church | Woolwich, Gloucester County | Founded 1799 in a free Black settlement; featured a trap door for hiding freedom seekers. |

| Queen of Angels Catholic Church | Newark, Essex County | First African-American Catholic church in Newark; served as NJ HQ for Dr. King’s SCLC. |

| Godwin Street AME Zion Church | Paterson, Passaic County | Founded in 1834, one of the earliest Black churches in North Jersey and a center of community life. |

| Shiloh Baptist Church | Trenton, Mercer County | Historic hub for Trenton’s Black community, now a leader in community health initiatives. |

| Bethany Baptist Church | Newark, Essex County | Founded in 1871, a strong and influential body in Newark’s history. |

| Mount Zion AME Church | Montgomery Twp, Somerset | Represents Black heritage in the Sourland region; future home of a museum. |

A New Generation Asks: Where Do We Go from Here?

Today, the Black church in New Jersey stands at a crossroads. The pews that were once filled with generations of families are seeing a shift. According to Pew Research, there is a significant generational gap in religious affiliation: 33% of Black Millennials and 28% of Black Gen Z identify as religiously unaffiliated, compared to just 11% of Baby Boomers. This isn’t just a statistic; it’s a conversation, a challenge, and a question of faith for the 21st century.

The reasons for this disconnection are complex and deeply felt. For many young people, it’s not a rejection of God but a critique of the institution.

- They see the church’s powerful history of activism and ask why it isn’t more vocal and visible in modern movements like Black Lives Matter.

- They crave authenticity and transparency from leaders, rejecting hypocrisy and judgment in favor of safe spaces where they can ask tough questions.

- They are pushing for greater inclusion, especially for the LGBTQ+ community. For Black Gen Z, a church’s acceptance of people regardless of sexual orientation is a top priority.

- Many are choosing a more individualized spirituality over organized religion, seeking a personal connection that feels more relevant to their lives.

But this is not a simple story of decline. Post-pandemic, some research shows a renewed search for community and meaning among young people, who are looking for stability in an uncertain world. The truth is, the current generational shift is not a rejection of the Black church’s legacy, but a

demand that the church live up to it in a contemporary context.

Young people are not asking the church to become something new; they are calling it back to its radical roots. Their critique is born from a deep respect for what the church was and what it still can be: a prophetic voice and an engine for liberation. In a way, their exodus is its own form of protest, mirroring the very act of protest that founded the first Black churches centuries ago.

Reimagining the Sanctuary, Reigniting the Movement

The Black church in New Jersey is a story of constant evolution. Its history of resilience, adaptation, and unwavering faith provides the blueprint for its future. As we stand at this generational crossroads, the path forward is illuminated by the legacy of those who came before us.

Key Takeaways

- The Black Church Was Born from Protest: Its origins are a powerful reminder that our faith and our fight for justice are inseparable. It was founded as a radical act of self-determination.

- A Legacy of Holistic Care: The church has always been more than a house of worship; it’s a pillar of community support, providing everything from education to healthcare. This model of comprehensive care is more vital than ever.

- The Youth Are Speaking: The questions and critiques from younger generations are not a threat but an invitation. They are a call to evolve, to be more inclusive, and to live up to the church’s powerful legacy of activism.

- The Mission Continues: The work of building a just and equitable community is far from over. The church, in whatever form it takes, remains a vital space for this sacred work.

Next Steps: What Can We Do?

The future of these foundational institutions is in all of our hands.

- For the Youth: Your voice is essential. See your questions as a continuation of a long legacy of pushing for change. Start conversations in your community. Join a church’s social action committee or use your digital skills to amplify the work of faith-based organizations.

- For the Elders: Listen with open hearts and minds. Create authentic spaces for intergenerational dialogue where young people feel seen and heard, not judged. Mentor the next generation of leaders and embrace new ways of connecting.

- For Everyone: Learn your history. Visit one of the historic churches in our state. Support the community programs they run. Recognize that the strength of our community has always been rooted in these sacred spaces, and it is up to all of us to carry that legacy forward, together.

The spirit of the Black church—a spirit of resilience, community, and unwavering faith in the face of injustice—is alive and well. It is a fire that has been tended for centuries, ready to be carried forward by a new generation, for a new day.

Who knew the Black church was such a versatile operation? Running the Underground Railroad one week and hosting SCLC the next? Impressive multi-tasking! But honestly, its no surprise younger folks are asking for a raise – the bar for activism is apparently set *really* high. Still, good to see theyre not abandoning the scene entirely; just demanding a more updated, inclusive model. Because lets face it, even in 2024, having a dedicated space for community uplift and pointing out hypocrisies sounds like a solid plan. The churchs evolution is key, and maybe we can all learn something from their centuries-long customer service record!basketball stars io

Thank you!