The Housing Crossroads: Brooklyn’s Fight for a Place to Live

If you’re a young person in Brooklyn trying to find a place to live, you know the ritual. You sign up for the city’s affordable housing lottery, you scroll through the listings, and then you see it: an “affordable” two-bedroom apartment that requires an annual income of $100,000. Or $150,000. Or even, in some cases, over $200,000. You close the tab, feeling a familiar mix of frustration and hopelessness. It’s a system that dangles the promise of a home but seems designed to tell you, quietly, that you don’t belong.

Now, imagine your grandparents’ generation. They weren’t met with a confusing website; they were met with a red line drawn on a map. That line, created by the government in the 1930s, declared their neighborhoods—places like Bedford-Stuyvesant, Brownsville, and Crown Heights—as “hazardous” for investment, simply because Black families lived there.They were explicitly denied the loans and opportunities that built generational wealth for white families across America.

The affordable housing crisis in Brooklyn isn’t some accident of the market. It’s the direct inheritance of this fight. The struggle has changed its face, from an overt “no” to a bureaucratic maze, but the goal feels hauntingly similar: pushing Black families out of the communities they built. The very blocks that were once starved of capital are now being consumed by it, and the stakes couldn’t be higher. This isn’t just about rent; it’s about the right to remain, the survival of our culture, and the fight for the very soul of Brooklyn.

Red Lines, White Flight, and the Architecture of Inequality

To understand why your rent is so high today, you have to look back to the 1930s. During the Great Depression, the federal government created the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC) to help stabilize the housing market. They did this by creating “residential security maps” for cities across the country, color-coding neighborhoods from green (“Best”) to red (“Hazardous”).

This wasn’t about the quality of the buildings. It was explicitly about race.

HOLC documents described Black communities as a “detrimental influence,” and the “infiltration of Negroes” was listed as a reason to deny loans. On the 1938 map of Brooklyn, huge swaths of what we now call Brownstone Brooklyn—Bed-Stuy, Crown Heights, Bushwick, Red Hook—were colored red. The message was clear and codified into federal policy: Black presence devalued property.

This single act set off a vicious, decades-long cycle of disinvestment.

- It Murdered Generational Wealth: By denying Black families access to federally-backed mortgages, redlining locked them out of homeownership—the number one tool for building middle-class wealth in post-war America. This created a wealth gap that persists to this day.

- It Invited Predators: With legitimate banks refusing to lend, a vacuum was created for exploiters. Real estate agents used “blockbusting” to stir up racial panic, convincing white families to sell their homes cheap, only to resell them to Black families at inflated prices. Others used “contract selling,” a predatory loan practice with impossible terms that stripped families of their homes and savings.

- It Justified Neglect: The “hazardous” label became a self-fulfilling prophecy. The city and private investors withheld funding for everything from basic services and school maintenance to housing upkeep, leading to disrepair and unhealthy living conditions. A line drawn on a map nearly a century ago can be directly linked to higher rates of asthma, hypertension, and even shorter life expectancies in those same neighborhoods today.

This system wasn’t just about housing. It was a strategy for economic and social containment, designed to create a permanent underclass whose consequences have compounded across generations.

The Great Inversion: From Redlined to Redeveloped

For decades, the legacy of redlining meant neglect. Now, in a cruel twist of fate, that same legacy has made those neighborhoods the hottest real estate markets in the city. The very disinvestment that starved our communities of resources for generations kept property values artificially low. This created the perfect opportunity for developers and speculators to swoop in, buy up land for cheap, and rebrand historically Black neighborhoods as the new, trendy place to be.

This isn’t just a feeling; the numbers tell a staggering story of displacement. In Bedford-Stuyvesant, the Black population decreased by 22,000 between 2010 and 2020, while the white population grew by 30,000. Over a similar period, median monthly rent in Brooklyn has skyrocketed, and the median price for a home is now a staggering $900,000.

| Neighborhood | Change in Black Population | Change in White Population | Median Rent Increase |

| Bedford-Stuyvesant | -22,000 (2010-2020) | +30,000 (2010-2020) | +31% (2010-2016) |

| Crown Heights North | Decreased from 78.1% to 44.5% (2000-2010) | Increased from 7.4% to 30.7% (2000-2010) | N/A |

| Bushwick | Non-white population decreased by 15.5% (2010-2022) | White population saw dramatic increase | +44% (2010-2022) |

| Williamsburg/Greenpoint | Non-white population decreased | White population saw dramatic increase | +78.7% (2010-2022) |

Export to Sheets

Data synthesized from sources.

This process is the final, profitable phase of redlining. First, the system devalued our communities to suppress their worth. Then, it acquired the devalued land. Now, it’s extracting maximum profit while displacing the people who were victimized from the very beginning. It’s a generational trap, and we’re seeing the second phase play out in real time.

The Affordability Paradox: A System Designed to Fail

When community members push back, city officials point to affordable housing lotteries as the solution. But for most Black families in Brooklyn, this system feels like a cruel joke. The problem lies in a broken formula called the Area Median Income (AMI).

“Affordable” rent in NYC isn’t based on the incomes of people in, say, East New York or Red Hook. It’s calculated using a regional AMI that includes some of the wealthiest suburban counties in the country, like Westchester and Rockland.This wildly inflates the number. As a result, housing lotteries often require incomes that are completely disconnected from reality. For a family of five, some “middle-income” units require an annual income of up to $227,500. This isn’t affordable housing; it’s a subsidy for the well-off that provides political cover while doing little for those most in need.

As if that weren’t enough, Brooklyn faces another ticking time bomb: the expiration of Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) agreements. For 30 years, this federal program has kept rents low in thousands of buildings. But now, those agreements are starting to expire, allowing landlords to flip the units to market-rate rents overnight.

Just ask the residents of 63 Tiffany Place in Carroll Gardens. For years, they’ve paid rents around $1,200 a month. With their LIHTC agreement expiring, they now face potential rents of $3,200 to $6,000—an eviction notice in disguise for families on fixed incomes. By the end of 2025, an estimated 30 buildings across the city could exit the program, pushing thousands of families to the brink. The very tools meant to create stability are now becoming engines of displacement.

The Frontlines of the Fight: Community Power in Action

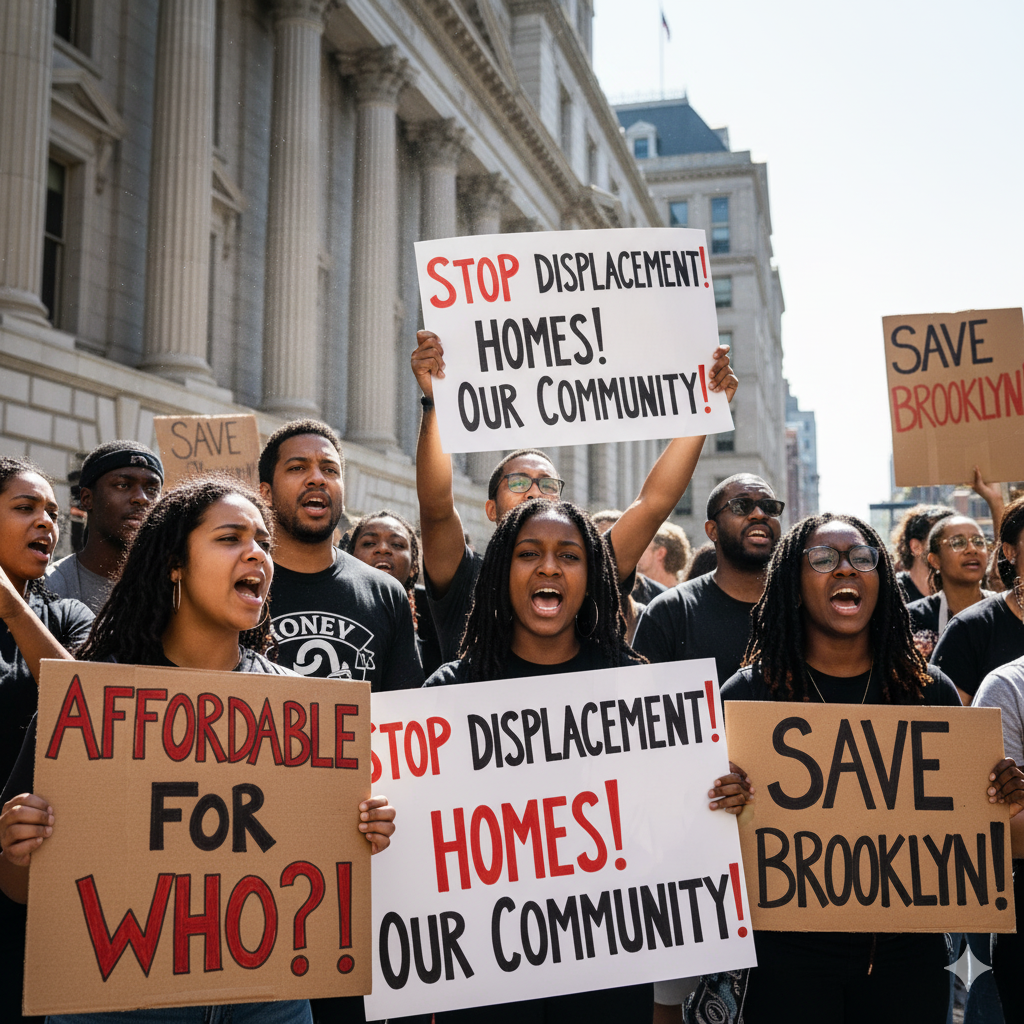

But Brooklyn is not a community that takes injustice lying down. Across the borough, a powerful movement of residents, faith leaders, and activists is fighting back with grit and ingenuity, proving that the most effective solutions come from the ground up.

- Faith and Foundation: In East New York, Pastor David K. Brawley of St. Paul Community Baptist Church is showing what’s possible when the community takes control. Witnessing his congregants being priced out, he and the East Brooklyn Congregations have leveraged church-owned land and organized power to build thousands of Nehemiah homes—truly affordable single-family homes that create pathways to homeownership and generational wealth for Black families. It’s a revolutionary model that says we don’t have to wait for developers; we can build our own future.

- Grassroots Resistance: When developers proposed massive rezonings in neighborhoods like Gowanus and Windsor Terrace, community groups like Housing Not High-Rises organized to fight back. They challenged the narrative that any development is good development, arguing that luxury high-rises with a handful of “affordable” units would only accelerate displacement. They showed up to meetings, presented alternative plans for more contextual and deeply affordable housing, and demanded that development serve the community, not just corporate profits.

- Tenant Power: From the tenants association at 63 Tiffany Place organizing rallies to save their homes to groups across the borough forming unions to fight neglectful landlords, residents are realizing their collective power. They are demanding a seat at the table and advocating for policies like the Tenant Opportunity to Purchase Act (TOPA), which would give them the first right to buy their buildings.

This fight resonates deeply with Brooklyn’s youth. For them, this isn’t an abstract policy debate. It’s personal. They’ve grown up watching their families struggle, only to see the neighborhoods they love become unrecognizable. Young people today are demanding more than just a cheap apartment; they’re demanding justice. They see the through-line from redlining to the flawed AMI and know that a system change is needed. The wisdom of elders who endured decades of neglect, combined with the urgency and digital savvy of a new generation, creates a powerful, intergenerational coalition that is redefining the future of Brooklyn.

Reclaiming Brooklyn: A Call to Action for a Just Future

The affordable housing crisis in Brooklyn is at a crossroads. The path we’re on leads to a borough of glass towers and cultural erasure. But another path is possible—one built on community, justice, and the fundamental right to stay home.

Here’s what we’ve learned, and how we can all be part of the solution:

Key Takeaways

- Historical Injustice is the Root: Today’s crisis is the direct legacy of redlining and segregation. It was designed.

- “Affordable” is a Broken Metric: The AMI system is structurally flawed and excludes those most in need. We need affordability defined by our neighborhoods, not by wealthy suburbs.

- Displacement is a Feature, Not a Bug: Gentrification and expiring subsidies are predictable outcomes of a system that prioritizes profit over people.

- Community is the Solution: The most powerful answers are coming from the ground up—from faith leaders, tenant organizers, and youth activists who are building the Brooklyn they want to see.

What’s Next?

The fight for the soul of Brooklyn belongs to all of us. Here’s how you can get in the ring:

- Demand Fair Standards: Call your city council member and demand they reform the AMI calculation to be based on local, zip-code level incomes.

- Protect What We Have: Support policies like the Tenant Opportunity to Purchase Act (TOPA) and advocate for the extension of LIHTC agreements to keep existing affordable housing permanently affordable.

- Support Community-Led Development: Donate to, volunteer for, or amplify the work of organizations like East Brooklyn Congregations and other local groups building truly affordable housing.

- Show Up and Speak Out: Your voice is your power. Attend your local community board meetings. Join a tenant association in your building. Register to vote and support candidates who have a real plan for housing justice. This is especially true for young people—your future is on the line.

This is more than a fight for a place to live. It’s a fight for who we are. It’s a fight for a Brooklyn where our families, our culture, and our communities can not only survive, but thrive. Let’s build that Brooklyn, together.

Related HfYC Content

- The New Redline Bridging the Digital Divide

- Northern New Jersey Black Businesses

- The Stories Our Neighborhoods Deserve

Other Related Content

- Official site for affordable housing programs and lotteries.

- Grassroots coalition fighting displacement in Brooklyn.

References

- Brookings Institution. (2022). The racial wealth gap and housing. – https://www.brookings.edu/articles/the-devaluation-of-assets-in-black-neighborhoods/

- National Low Income Housing Coalition. (2023). The expiration of LIHTC and its impact on tenants. – https://nlihc.org/resource/end-lihtc-affordability-restrictions-looms-over-tenants

- New York City Department of Housing Preservation & Development. (2024). Affordable housing and AMI guidelines. – https://www.nyc.gov/site/hpd/services-and-information/area-median-income.page

- Sugrue, T. (2014). The origins of the urban crisis: Race and inequality in postwar Detroit. Princeton University Press. – https://press.princeton.edu/books/paperback/9780691162553/the-origins-of-the-urban-crisis